Volunteering with Wildlife Agencies

- by 2%’s Executive Director, Jared Frasier

A little over a week ago, I received an email that I’d been waiting on for many years: An invite to help with an alpine native trout genetic sampling project!

While fish genetic sampling projects can take many forms (netting, hook’n line angling, trapping, etc.) the most common way to go after alpine or small stream fish involves a backpack with a battery to shock the fish… but we’ll get to that in a second.

Part of earning 2% Certification is to give at least 1% of one’s time to fish and wildlife conservation. For most folks, especially with the challenges this year has thrown at us all, getting out and cleaning up your local trails and waterways will be the ‘most extreme’ and meaningful way they can give back to wildlife. And even then, scheduling organized cleanups has been very difficult, if just from a liability and contact-tracing perspective.

And yet 2020’s challenges have brought about some unique opportunities - in part - thanks to the pandemic.

We’ll get to that, but first, here’s a little background info.

Most wildlife management agencies have depended on inexpensive seasonal help from contractors and students to collect fish and wildlife data for decades. This is true, virtually around the world.

With regional, state, and federal wildlife management agencies experiencing repeat budget cuts from their government bodies, at a global scale, this need has only grown in the past decade. In the last few years, that funding decline has been sped up in many US states as they struggle to prop up aging and emerging industrial revenue streams at the same time. For example, the state of Wyoming has officially one lone lobbyist for wildlife in their legislature - 2% Board Member, Jess Johnson. With so few folks advocating for dollars to go to wildlife management, in the rooms where budgets are decided, it should be no surprise that the agencies repeatedly get the lame end of the deal. This makes them less able to hire staff or contractors to help with field work. And, I’d like to note: No one gets into wildlife management agency work to get rich. It’s one of the lowest-paying career paths you can find.

Now, add a pandemic that shuts down universities and limits how many wildlife-focused students can move to an area for their education… and you’ve lost another subset of your labor force. This time, the free help - and the next generation of agency employees. While 2% wasn’t built to help with the latter, we can help with the former.

Thankfully, despite what you might read from the armchair ‘conservationists’ in online comments sections, wildlife management agencies can be pretty quick on their feet. Decades of exponentially growing and conflicting expectations from the public, paired with repeat budget cuts, have made them so.

While the bulk of their work requires tasks that absolutely require special training and immersive education, many agencies have started looking to citizen volunteers for assistance. Specifically with wildlife data collection.

That said, if opportunities in your area haven’t been widely broadcast, there are some good reasons.

Opening the door to volunteers has its caveats:

Volunteers require extra, often one-off, training.

You don’t always know what kind of person you’re getting… did Chucklehead McJerkface sign up?

Can these volunteers follow directions and stick to the project parameters… or will they flake out and bail on you when the going gets challenging, like so many folks are prone to do?

Most importantly, will the data collected still be as accurate?

From my conversations with field biologists from multiple jurisdictions, that last point is the most concerning.

If this year has taught us all anything, it’s that the only thing worse than no data is bad data. The downstream effects of bad data can lead to decades of wildlife mismanagement.

Yet, with those factors in mind, many wildlife management offices are opening their projects up to volunteer lay-person involvement.

Why? Because the work must still be done. They need the data. Ecosystems don’t hit the pause button just because of budget cuts and pandemics.

Also… it turns out that volunteers are actually really, really useful for a wide range of tasks…

Example #1: Elk calf population surveys in Wisconsin.

Let’s say you’re an absolutely financially gutted wildlife management agency in a midwestern state and you’re trying to bring back one of your state’s largest historically native species: elk. You’ve got a great conservation partner in the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and the buy-in of most of the locals. Your state gave the thumb’s up on the effort… but didn’t give you the necessary funds for keeping tabs on the herd. Oh, forgot to mention, they’re not being brought back in the southern prairie part of your state. They’re going to be in Wisconsin’s insanely dense Northwoods.

You’ve got radio collars on as many adult elk as you can manage, but that only tells you how many adults are alive and roaming around… How are you supposed to keep tabs on each year’s newborn calves? How are you going to count any new calves every spring? The forest is far too dense for flyover surveys. You don’t have the budget for contractors. The UW Madison is 5hrs away and will kick some students your way for a lot of things, but not at this scale.

What you need is an army of free labor that can grid-search for calves. An army of volunteers that will listen to your instructions and who want to see the elk succeed as much or more than you do.

That’s exactly what RMEF members have provided the WI DNR, multiple times a year, for the last few decades:

Example #2: Rocky Mountain Goat Alliance Surveys

It’s hard to think of a more dramatic and near-immediate example (we hear you, yelling from the back, waterfowl banders!) of what coordinated volunteers can mean for a species. Rocky Mountain Goat Alliance (RMGA) surveys are some of the most extreme, yet rewarding, volunteer opportunities to partner with wildlife agencies on. First off, consider the species. It’s a damn mountain goat. Their preferred habitat starts at 8,000ft (2,400m) above sea level and goes all the way up until they run out of nasty cliffs and scree fields to hug. “But they have their young down lower, right?” Nope. Those little fluff balls play with 1-2 story drops like they’re a child’s bumbo seat.

So when a wildlife agency needs to do a survey, the do it almost exclusively from the air. There are shortcomings to air surveys though. Firstly, you don’t see everything. Goats notoriously like to hide in the darnedest places, especially the young. They also blend in really well with snow (duh) where they like to bed. And, contrary to what your energy-drink-crushing college roommate with a sled might’ve anecdotally shared, they usually run like a bat outta hell from the sound of a motor.

Not getting accurate counts, especially of nannies, yearlings and kids, can have a very negative impact on population management for wildlife agencies and human recreation management for land agencies. Just a few years ago, I sat on the phone with a local US Forest Service office, exasperatedly trying to explain that there were goats being pushed out of an area that was becoming popular with a local snowmobile club. The most recent winter data that their office had was from the 1980’s. Why? Flights are expensive and goats were a low priority for their gutted budget.

2% Committee Member, DJ Zor with some goat fluff from one of RMGA’s surveys this summer.

But that paradigm is changing. Less than a decade ago, the Rocky Mountain Goat Alliance was started up when a bunch of hunters volunteered to do a pilot-project population survey in partnership with Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks in a mountain range where goats were thought to be dwindling. While the data collected could have proven the assumption right… it didn’t. The population wasn’t shrinking - it was higher than previously expected! The group now hosts several every summer across multiple jurisdictions in the species’ native range.

It’s not for everyone, though. While not requiring as many people to ‘grid search’ the mountain ranges (you let your eyes do as much walking as possible, via scopes and binoculars) it does take at least a dozen people in pretty good shape and with some backcountry skills and safety knowledge to make a survey effective. There has been one volunteer death, due to a fall a few years back (and the group has taken great pains to remove risks since then). People need to be ok with not seeing goats and reporting that accurately. There is no place for ego in data. Inflating your numbers can lead to inaccurate management decisions that ultimately negatively impact the population.

All that said, it’s an immensely rewarding experience to be a part of! If you have the opportunity to get in decent shape and travel to a western locale for one, I highly recommend it. I’ve done surveys in three mountain ranges with RMGA, including one with my son, last summer.

Some RMGA surveys, especially ones taking place closer to human population centers or the Black Hills, offer opportunities for ‘kids to count kids’ - like this one I did with my son in the Bridger Range near Bozeman, MT last summer.

Bonus points for figuring out how to tell this photo is from 2020…

The surveys have also been supported by several 2% Certified Businesses, with companies like Alpen Fuel using the opportunity to get their required 1% of employee time donated in one fell swoop. You can read about their experience from this year, here.

A standout business in supporting the efforts has been Stone Glacier. They have hosted nearly all volunteer training sessions at their offices for the last few years, and provided 1-to-1 advice on alpine safety, gear tips, and personal stories of goat encounters to help the volunteers.

You can learn about future survey opportunities with RMGA by visiting their site and signing up for email updates, here: Rocky Mountain Goat Alliance

Example #3: “Hey locals… who wants to help?”

That’s pretty much what the social media post from Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks said. They posted in an Instagram story that they had some opportunities to help the local fisheries program and were looking for folks to add to an email list.

This was new. In years of volunteering with them in various capacities, I’d never seen a callout like that… but I’ve been hearing about them happening across the US and Canada for all the reasons I laid out at the start of this blog post. Naturally, I signed up. I did so, selfishly, because I think about fish… pretty much all day. I also wanted to see how it would go, and if it was something I should recommend to our followers and members.

Hot dang, y’all, am I glad I did!

Within a few days, I received an email from the local office, “Can anyone help with a couple genetic sampling projects for westslope cutthroat trout next Tuesday?”

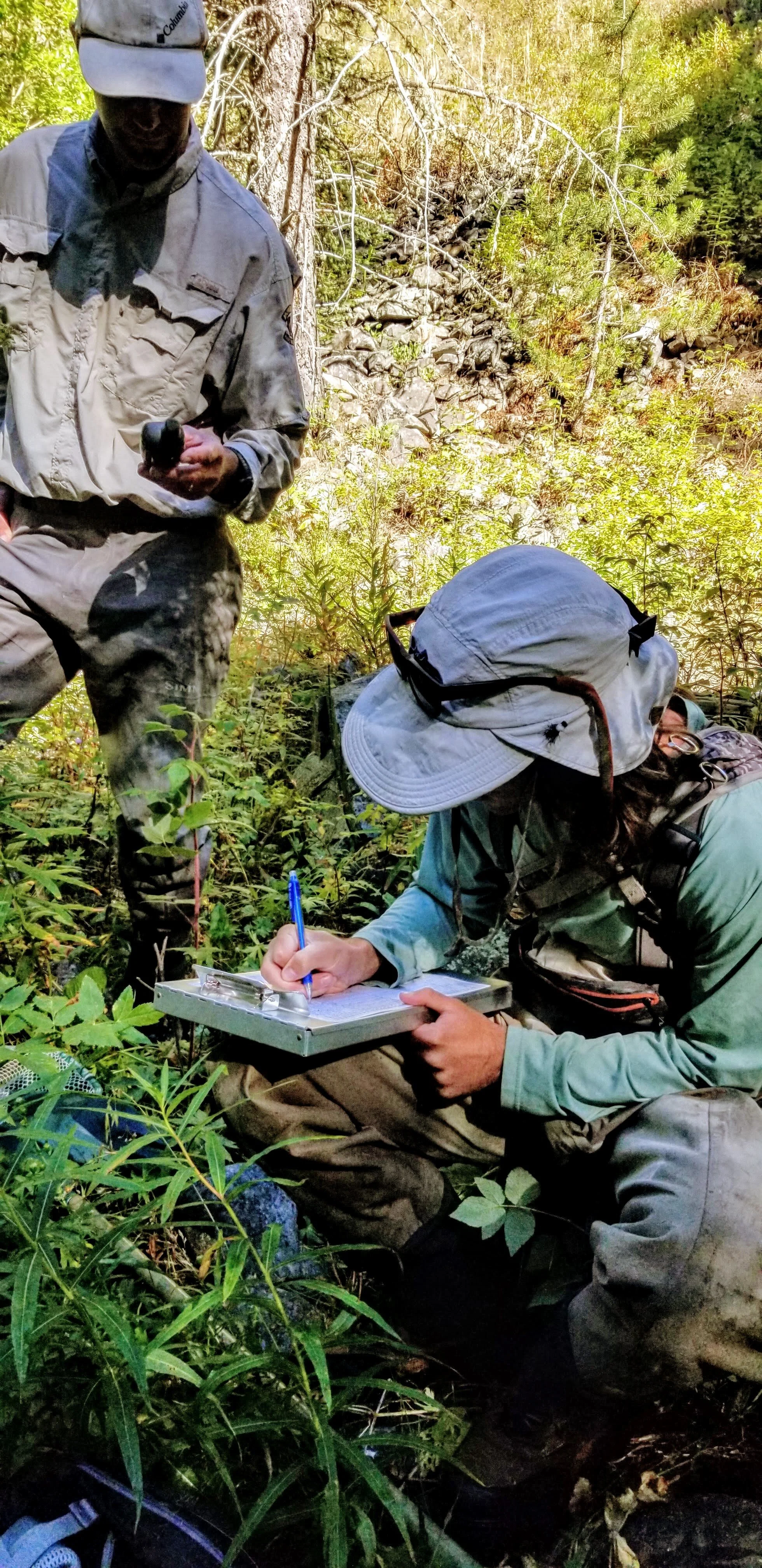

Four days later, I was in the local FWP office parking lot, queueing up with a bright eyed Montana State University student (who wasn’t there for a class requirement - he just wanted to volunteer) and a fisheries technician to head up into the mountains for the survey.

It was one of the best ways I’ve ever spent a day.

I’ll leave you with a few photos down below, but to explain how these projects work, I’ll leave that to the pros - namely, Marcus Hockett of the newly 2% Certified Randy Newberg’s On Your Own Adventures. They did a whole video on this, and you can see how a thoughtful and willing-to-listen/learn volunteer like yourself can be an asset to your local wildlife management agency… and maybe even get to fish while doing it!

In the case of my day volunteering on a genetic sampling project, we used the electro-shocking method. This was something I was keen to see in-person, as I’m a borderline nut when it comes to advocating for not stressing fish during the summer (many caught and released fish die from the experience, after the angler moves on).

The fish were shocked, very gently, and the technician we worked with consistently checked to make sure we were using the right settings for the size of fish and the particulate levels in the water.

While each trout needed to be removed from water, just briefly to snip a tiny fin sample, great pains were taken to keep them wet and happy with frequently refreshed water the entire time. They were also ‘drugged’ with an all-natural and safe solution of featuring clove oil… maybe ‘briefly drunk’ is a better word for their experience - a state from which they very quickly recovered.

You can tap on an image to expand:

Getting to some of the sampling locations was a little bit of a challenge, especially in waders and carrying all the equipment, but I think anyone of average fitness would be just fine. The important thing is to listen and follow instructions very closely - both for the sake of the fish and the quality of the data.

The technician we worked with stressed that not all sampling days go as pleasantly as the one I participated in. You may not find fish. You might have to go much, much further. In some cases, he said, the physical demands are more than an agency would like to request of a one-day volunteer. The weather and insects can make it very “why am I doing this” uncomfortable. These are all things one should consider before signing up to volunteer.

But sign up, you should.

2% for Conservation was founded to help businesses and individuals bridge the gap between the ever-growing needs of fish and wildlife and the capacity of those who work to grow and improve species population health around the globe.

Here’s what you can do:

Look up your nearest regional wildlife agency office.

They might be under the name of “[Your state/province] Fish and Game”, “[Your state/province] Parks & Wildlife”, “[Your state/province] Department of Natural Resources”, etc.

Ask to be put in touch with the person who handles the species/habitat projects you are passionate about.

Let the person answering the phone know that you’re calling to be a help, not just another complainer.

Ask “Do you have population or genetic survey volunteer needs for [name of species]?”

This will probably confuse them. Again, most folks call to complain or ask for free info. They’re not accustomed to being offered help.

If they don’t have an answer for you, say verbatim, “I would love to help out sometime. I know you have a massive work load. If I don’t hear back from you in the next few months, I’m happy to reach out again to offer my help. Thank you for all you do for [name of species/habitat].”

There is a pretty strong chance they will either recommend partnering with a local conservation organization or ask if you are a member of one. If you aren’t, join one. As long as the group has a good reputation with their offices, those memberships can open up a lot of cool opportunities to collaborate with your local wildlife management agency.

And if you are looking to set up a volunteer day for your business and making those calls sounds like a lot of work, that’s what our Committee Program is for! They can help you get connected with ways to give back in your area that are pretty plug’n play: Committee Directory

The important thing to remember is that these wildlife agency folks are working hard for the species you love - year round.

Whether or not you get an opportunity to volunteer with them, they need your support!