How to volunteer your time for wildlife - Part 3/5: Habitat Improvements

By Jared Frasier, Executive Director

In our first two installments, we looked at habitat cleanups and wildlife counts, which are great ways to volunteer your time for wildlife. Whether you are looking to start volunteering on your own, or as a company, both are great starting conservation activities!

Part three of our five-part wildlife volunteering series is focused on habitat improvements.

For many of our business members, improving wildlife habitat is a core value in their company culture. Unlike brands who have nebulous “why” statements (“We at Stalegorp Corp. exist to make the world a better place.”), brands that center their “why” around real-world projects and engage in the work themselves actually fulfill their “why” statements. It takes time. Volunteered time. But the results of putting yourself and your team into a landscape and investing your time and “sweat equity” are undeniable. We love it when a business reaches out asking how to start doing habitat improvement projects — it is always the start of something incredible!

An important consideration before we begin: As with all volunteering for wildlife, we recommend that you partner your business with a non-profit conservation group that specializes in the kind of project you want to do. Even if you intend to do the project on your own, their expertise can be invaluable.

Why?

In many places, permits and agency oversight are required for habitat projects — even on private land. And they can be challenging to acquire. On top of that, lawmakers change landscape management policies all the time, sometimes with little public input and little to no warning. We will get into fixing that when we cover volunteering your time for wildlife through advocacy.

Conservation groups have paid staff and volunteers who know the local landscape and wildlife policies. They often have several people dedicated to the very work you hope to volunteer your time doing. At a minimum, partnering with a conservation group will help you get through red tape quickly, with the added bonus of their direct expertise in the project you are pursuing.

Beyond informational help, many conservation groups also have resources to help you tackle the habitat project more efficiently. Many groups, and specifically land trusts, have paid staff that can do an in-depth audit of the existing flora and fauna, as well as the potential of a habitat area to be placed in a conservation easement — conserving it forever. Species-specific and ecosystem-specific groups typically have written grants for academic studies on the species and ecosystem you are looking to help. Many groups have access to physical assets for habitat projects. They know where to get seedlings, bare root stock, prescribed burn tools, and any other special tools or licensed professionals required for a project.

The most obvious help they can offer (if you do not have a habitat area selected) is where you should put together a habitat improvement project and what kind of project it could be. Even if you are operating on private land, their knowledge will add significant value to your volunteered time.

With that in mind, let’s look at some of the popular ways 2% Certified brands volunteer their time doing habitat improvement projects.

To keep it simple, we like to divide habitat improvement projects into three categories:

Rewind

Renew

Rebuild

(folks remember things in “3’s”)

Rewind (the damage)

First, let’s be honest. You cannot ever fully rewind the damage humans have done to an ecosystem. The simple act of walking through a forest changes it forever. So does flying at 36,000 feet over it. So does an industrial plant upwind or upstream from it. You cannot exist on this planet without causing harm to something wild, somewhere, in some way. Period.

All living things are in competition with each other. But only humans are capable of causing immense change at a rate that no other species above the microbial level can keep up with. Entire ecosystems have ceased to exist so that you can read this on whatever device you are reading it on. The same is true for the device it was typed on. And the infrastructure required to power both of our devices, the servers this text lives on, and the vehicle you are pondering using to drive to therapy after the existential crisis of the weight of your modern existence hits you.

The planetwide ecosystem-changing mechanisms that modern society is built on are far too big for you or any single business to tackle. But this is not a license to “let it ride” — hoping that nature will heal itself. It cannot “heal” without help, because every ecosystem is connected to another. It is why, time and time again, hands-off ecosystem-wide preservation policies fail. Leaving an ecosystem alone, while the the ones around it are infested with human-introduced invasive species, or have aggressive fire-suppression policies, or have shipping lanes passing through them… you can see the guarantee of the ecosystem being damaged even if we do not directly “touch” it.

So what do we mean by “rewind the damage?” It is simple: Give wildlife a chance by reducing or removing negative human-caused impacts in an ecosystem. Small actions, collectively moving towards a larger goal.

A prime, continent-wide example from North America is bad fences. For the last few centuries, North America was carved up and quartered off by ever-segmenting private and public land parcels. Less than 200 years ago, there was nothing man-made physically separating wildlife populations from each other. Pronghorn, mule deer, elk, bighorn sheep, and bison made huge seasonal migrations. Some, over hundreds of miles and through multiple diverse connected ecosystems. Everywhere they went, they impacted those ecosystems in ways unique to each species. But those migrations slowed, and most stopped altogether, as people started putting up millions of miles of barbed wire and tight-grid sheep fencing. Never mind what the strip-mining of entire mountains for metals to build the fences (and the electrical wiring that followed) did to Northern Minnesota, the U.P. of Michigan, and across Northern Appalachia and New England. It was catastrophic. The landscape will never be the same. Ever. Even if every human left North America, the fences would remain for hundreds to thousands of years, thanks to weather-coating and other processes used to ensure the fencing does not need replacing.

But, we can start to rewind the damage.

At the end of 2020, we received a request from a regional field biologist in Southwest Montana. She had been tracking pronghorn movements with radio collars for a couple years. Their tracks on the map revealed a pattern she had observed, but needed verified proof of: Pronghorn herds were trying to migrate with the seasons, only to run into fences and get stuck on various ranchers’ lands. Many times, they were stopped short of getting to good feed, and with summers trending hotter and dryer, the herds were in trouble. Those that did not get stopped had huge gouging tears in their backs.

What was doing this to them? Century-old sheep fences and barbed wire. Much of which were decades from their last use. All of which could use an upgrade to wildlife-friendly fencing.

She wanted to apply for a wildlife migration grant through the National Wildlife Federation, but the federal grant program NWF was signing for required matching funds. Here was the cool part: Some of those matching funds could be provided in the form of volunteer hours. It was a real, “Time + Money = Fish and Wildlife Conservation” kind of scenario. The stuff our members excel at!

We got on the phone and hit our member lists hard. She needed to have the time and dollars guaranteed by the end-of-year deadline, only two weeks out from her initial call. We are so proud of our membership — they beat the deadline by a week.

Over the course of 2021, 2022, and 2023, our membership volunteered hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars to this project. They removed several miles of century-old bad fences and where needed, replaced it with wildlife-friendly fencing.

Pronghorn stuck behind bad, outdated fencing, unable to follow their migration route to green feed. This video was taken from within the project area.

Several of our business members and individual pledge makers traveled from all around the country to help replace or alter fencing to make it wildlife-friendly. Clark Dodd of Bella’s Bones came out for three days of work, a couple drove up from Las Vegas, another pledge maker flew in from Pennsylvania, and business members poured in each week from around the N. Rockies in partnership with local conservation chapters and groups.

While multiple groups spent time working on this project, one particular 2% Certified business went way above and beyond. In both 2021 and 2022, a team from River City Tile and Stone drove from the Twin Cities in Minnesota, all the way to Southwest Montana.

Each time, they spent multiple days spooling up the piles of old fencing collected by previous crews, using their company skid steers that they brought all the way from the Mississippi river to the Northern Rockies.

“Engaging in conservation projects has been part of my life since I was a kid, and I’ve always enjoyed doing them. As an adult and business owner, I’ve been lucky enough to be able to introduce conservation projects to key employees, and the outcome of doing that has been outstanding for our culture, and all of us personally.

The migration corridor projects, in particular, are a great way to get people involved. There’s tangible data from collar data that I can use to show them the why. When they get their hands on that barbed wire, they can see it and feel it. The sense of accomplishment at the end of those projects is overwhelming. It’s all smiles and laughs, and thank you’s.

Hauling all of that equipment from Minneapolis to the Rocky Mountain West is not inexpensive, but I can justify it with my own passion and the experience I get with employees. They’re working their asses off out there, and loving every minute of it. We talk a lot about getting kids involved in the outdoors. This is a unique way to get adults involved as well.”

You can read up on Mike’s team’s exploits, here.

This is just one example of a “Rewind,” style project, and there are many wildlife migration projects in need of volunteers around the world! Other examples, just from our membership include:

Replacing old culverts under roads to allow streams to always flow along their natural course.

Helping design wildlife overpasses to allow natural movement and migration over busy roads.

Building beaver dam analogs (building small natural dams the way a beaver would) to hold water at elevations where beavers have been eradicated.

Removing unused or fixing used trails so that they do not cause erosion.

Removing outdated and unused human infrastructure (like old dams) from rivers.

Making abandoned ocean rigs safer for the aquatic species that congregate to them.

The sky is the limit with this kind of project. Rewinding the damage of human infrastructure impacts is an incredibly rewarding type of project to work on.

But what do you do if an ecosystem has been impacted by human-caused species invasion?

Renew (the natural processes)

Renewing the natural processes that keep an ecosystem from crashing really just means to manage the competition between species. Naturalists and ecologists have long argued about if there is a “natural balance” in nature that we should strive to enable or return to. The real answer is, there isn’t… but there also kind of is.

When everything is competing on something of a metaphorical level playing field, it can look like equilibrium. Even in the most “balanced” appearing ecosystems, it is a collective struggle to the death to out-perform everything else. We love hearing about simbiotic relationships, because they sound nice. The reality is, every living thing is trying to take as much as it can for as long as it can in as many places as it can so it can reproduce as many of itself as it can. Your inlaws were not the first to try that!

Species are always pushing into new territory. Even the most sedentary (plants, trees, coral, barnacles, etc.) try to send their offspring as far away as they can. Some species spam the reproduction button (again, not talking about your inlaws) to try to overwhelm the local ecosystem with their young to ensure enough survive to do it all over again. Look at the giant cicada hatches happening this year (2024).

There is typically enough pushing and shoving to make it look like a “balance,” for at least a little while.

When humans move a species from somewhere it has predators or seasonal factors helping suppress its numbers, you can collapse an entire ecosystem. And sometimes, there is no way to get rid of them. Lionfish from the South Pacific will never be completely removed from the Caribbean and the ecosystems will never be the same because of it. The only option is to slow the death of the ecosystem by killing as many lionfish as possible. Hopefully, slowing the change down enough will allow the Caribbean ecosystems to turn into something new on a timetable that does not equate to catastrophic collapse. It is sad, but that is the reality.

But sometimes, there are things you can do. Especially if the species that is threatening an ecosystem has a weakness that the native flora and fauna do not have.

On land and in freshwater, there are two natural landscape “hard reset” mechanisms (albeit, on a limited scale) that humans can use to purge an ecosystem of unwanted usurpers. Around the globe, before agriculture replaced hunter-gatherers in a region, they were the only real tools used to ensure an ecosystem could remain healthy enough to support humans. In the pre-colonial Americas, they were both used by indigenous people to create huge food forests and abundant waterways.

What are the two natural mechanisms humankind has used?

Fires and floods.

Now, if you are an anthropologist, please do not send hate mail for the oversimplification. We are not saying that everyone everywhere always did controlled burns and/or intentionally flooded lands to manage species. We are saying that a lot of people did, and a lot of people still do. But clearly, in the last couple hundred years, more people decided not to. Gonna need you to climb all the way off our backs on this.

Remember at the beginning when we said you should partner with a conservation group for habitat projects and the necessary permits?

DO NOT TRY TO BURN OR FLOOD ANY HABITAT AREAS WITHOUT THE PROPER PAPERWORK!!! A quick search on YouTube or TikTok for “prescribed burn gone wrong” will provide you with hours of footage as to why.

So what makes fires and floods useful tools?

It depends on where you are in the world, but essentially, it boils down to leveling the playing field for the species you want to survive in an ecosystem.

Controlled burns kill any plants or bugs that have overtaken a landscape while also making it possible for other species to reproduce or spread out through areas that were overcrowded.

They typically occur naturally in wooded and prairie ecosystems. The species there evolved to survive them, by one way or another.

Note that we are not stating this about wildfires in general. Human development, forest policies, and fire suppression have made that a can of worms for people far more qualified to address somewhere else.

Flooding (directed irrigation) washes away or drowns species that thrive when not flooded and allows the reproduction and expansion of species that do benefit.

They typically occur naturally in desert and seasonally arid ecosystems. The species there evolved to survive them, by one way or another.

Note that we are not stating that all floods are “good” for an ecosystem. One need only to check the news to see how human infrastructure has made floods more prolific and catastrophic than they were before the rivers were channeled and rerouted.

Far and away, the most commonly used natural tool used for ecosystem renewal in North America is the prescribed burn. Every land-based species native to the woodlands and prairies in North America have evolved some adaptation to procreate after or through fire. That includes the fauna, not just the flora. Any hunter who has hunted a burn will tell you… well, wait… if they are smart, they probably won’t. The best, most nutritious feed for wildlife grows up through the ashes of a burn.

Controlled burns are something several of our business members send their employees to volunteer on at least once. With the noted exceptions of the businesses whose jobs typically involve putting on burns, employees of our members always volunteer with a local land trust or wildlife habitat group for these. It is just too much of a liability to take on as a business - even if it is on your own land.

To ensure you are attending or sending your employees along with a knowledgeable and experienced group, do these 4 things:

Ask to see a project area from one of their past burns. If it is a few years old and is either still covered with thick shrubs or is completely dead with no evidence of anything green growing on it, you might want to look elsewhere.

Ask who they get their permits through, and then confirm it with that office. Listen, sometimes mistakes are made. But this is an avoidable, high-liability one.

Contact your local agencies to see if they are hosting any burns that you can help as a digger or raker on public lands. It is a great way to gain experience as someone who is essentially free manual labor.

If there are no groups in your area with opportunities to join a burn, or you want to find out the right steps for your own burn, contact your county office. They can set you on the right path to getting one set up with the right agency or group.

Hack: Want to save even more time? Ask a farmer or a rancher what steps they have to go through for theirs. Odds are, if they have pasture land, they do a burn every once in a while and have a quick “in” to get you through the paperwork faster.

Just so we have made it abundantly clear, this is a volunteer activity with risks. If you know that before going into it and treat it as such, you can have a safe and highly effective burn. The plants that come up afterward are going to be some of the greenest you have ever seen and the landscape will be SO healthy!

So what about controlled flooding?

In the US and Canada, the most common form of controlled flooding is building beaver analogs. Essentially, teams go up into riparian zones and cut down sticks and logs to pack with mud and sod, damming a small stream. These create pools that help hold water through the hot months of summer and renew long-dormant riparian ecosystems over the course of a few months to a few years. Sometimes, it creates a habitat which beavers can be reintroduced into. Because of the over-trapping of beaver and loss of beaver habitat in the North American West, there are fewer ponds high in the hills and mountains holding water into the heat of summer. It is a leading cause of desertification of creek biomes that used to be lush, all summer long.

Controlled flooding for wildlife is still much more common in other parts of the world but in completely different ways.

Desertification is a growing ecological disaster, all around the world. But, few places have been hit harder than countries in eastern Africa like Tanzania and Kenya. Huge ecosystems have nearly collapsed in the last couple of decades due to loss of flora and the increasing heat and dryness that compound the issue. However, they still get some seasonal rain. Instead of beaver analogs (because they never existed there), conservationists are digging thousands of half-moon-shaped holes in the ground and pile the dirt on the “curve” side. These holes collect water and hold it long enough to allow dormant seeds to reawaken. Insects move in next, followed by birds and other small pollinators and seed spreaders like rodents. Within a year or two, what was once desert is now lush and green!

Indigenous groups in North America had a similar practice and some of our members in the Southwest United States have been testing these methods to slow the desertification in the foothills above arid deserts. Similar to the African projects, the Southwest receives monsoons every year. Capturing water is the key to renewing what was lost in those regions.

Several of our business members have sent employees into the desert to volunteer with groups like the Fraternity of the Desert Bighorn, installing “guzzlers” - basically, large water collection systems deep in the desert that replace lost water resources for wildlife.

Unlike controlled burns, you might not need a permit to do water-related projects on private land. However, some local governments have very strict rules about water collection. Make sure to find out what yours are — they are getting very serious about the fines for illegal water capture!

Rebuild (what was lost)

You might think that you need to own some serious acreage to rebuild an ecosystem. A lot of folks think they need to acquire land or work with a land management agency to make an impact.

However, if you have a touch of ambition, stout resolution, and even just an office flower bed or window box — you can rebuild lost habitat!

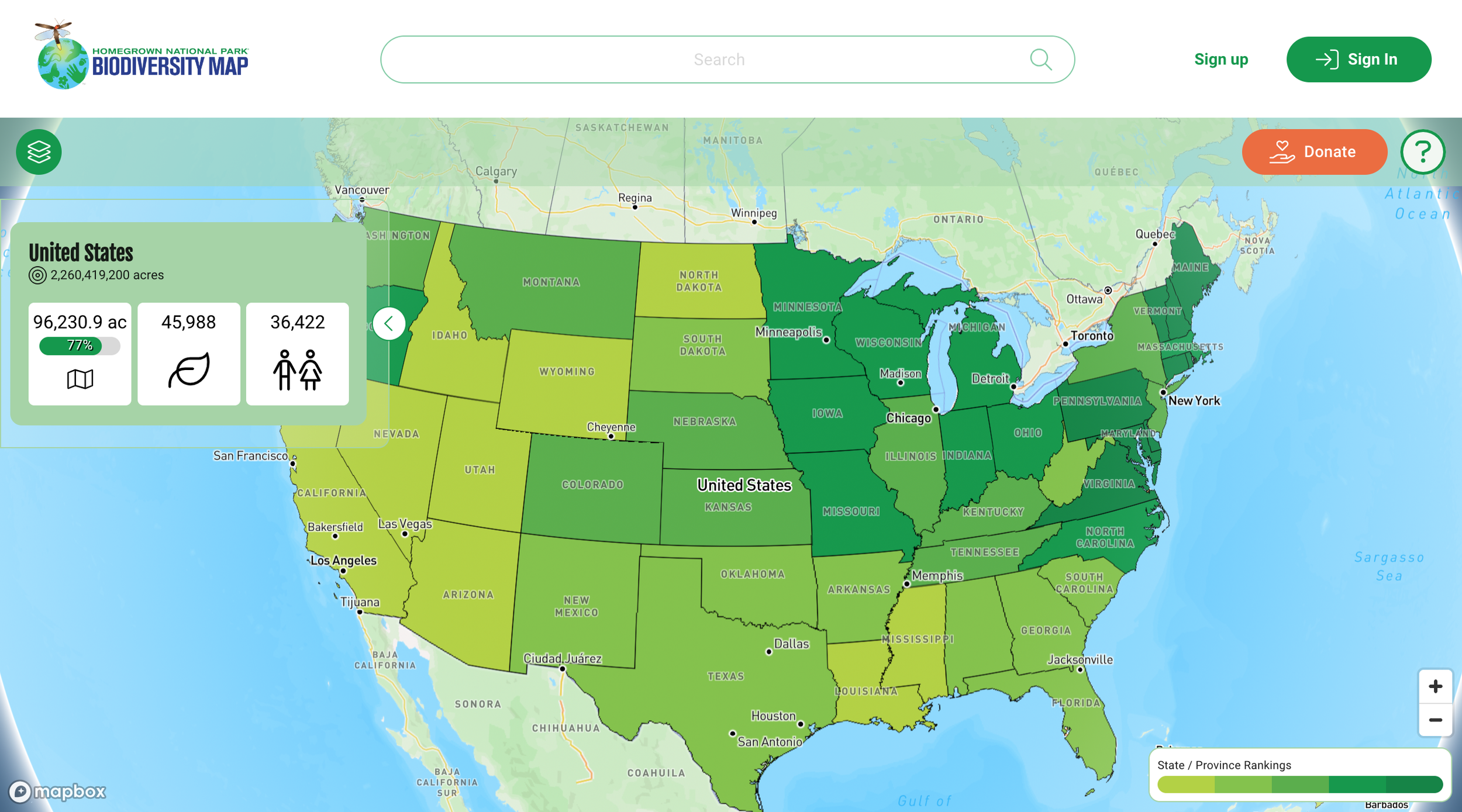

And the scale really does get that small, thanks to the work of groups like one of our Community Partners, Homegrown National Park.

Before we get to the big habitat stuff, go hit up their website. They are undertaking the largest private native habitat restoration project ever attempted… and it is working!

Essentially, the idea is that providing whatever amount of native flora that you can to local wildlife will help close the “pollinator desert” gap, rehabilitate our native insect and bird populations so that they can compete with the invasives, and stitch together a network of micro-habitats to help rebuild our ecosystems before they collapse entirely. You can do this by something as small as planting native plants in a window planter, in the landscaping around your business, all the way up to several-acre plots of land you may own or operate on.

Using your time and your dollars, you can have a direct positive impact on native wildlife by planting the nutrients they evolved to interact with… instead of the introduced shrubs, trees, and plants that invasive bugs, birds, and rodents evolved to interact with elsewhere.

Again, it can be as small as buying and maintaining a single flower pot. Homegrown National Park has links to seed banks to collect native plants for your area. You can also, in the USA, reach out to your local conservation district or land trust as they often have stores of native seeds, seedlings, and bare-root options.

If you have a landscaping company handle your business's landscaping, you may have to help them source the plants. Most landscapers are looking for plants that aren’t necessarily native but are easy showy growers.

Now, if you do have some acres to play with, we recommend (a third time, now) that you connect with either a habitat-specific or species-specific conservation group to help you assess what you have going on on your land. That is unless you have a 2% Certified arborist or ecological engineer near you. Getting a full inventory, map, and general assessment of your property’s potential is not only prudent for the up-front savings that come from choosing the right management decisions for your property — it also gives you an idea of what is possible in the future.

Several years ago, Mark Haslam’s family’s South Carolina land was in rough shape. It had been heavily used and abused for agriculture and, by many metrics, could have been seen as a lost cause. Thankfully, Mark’s family had a vision for what it could become. Over the course of multiple years, and with a lot of sweat equity and real equity, they were able to rebuild the land into some incredible habitat for several species.

A few years ago, Mark and his family won the National Deer Association Habitat Steward of the Year award, in recognition of the work the family had put into the ecosystem. An ecosystem, we should note, that they have been intentional about providing access for underserved communities to learn about conservation in a hands-on way.

“Habitat improvement has been vital to the overall health and success of game species at my family farm. Through years of prescribed fire, TSI [timber stand improvement], and drastic chemical reductions, we have boosted wild quail numbers to a stable population, brought back turkeys to a pine farm and improved deer herd age structure.”

Depending on where you live, your starting point for rebuilding lost habitat can vary. In most of the country, starting with Homegrown National Park (HNP) and your local land trust are universally good choices. Use HNP to get a rough idea on what plants you should support, burn the ones you shouldn’t, and then look into a conservation easement with the land trust.

If you do not have a decent land trust in your area, or if your ecosystem is significantly different from what you can find on HNP, reach out to a species-specific organization. If you have coastal property, even on a lake, talking to professionals from a clean water or aquatic species conservation group will help you do good by your land habitat and your aquatic habitat.

As always, we love helping businesses find creative and meaningful ways to give back their time to wildlife conservation. If you reach a dead end in your search for information, just reach out to us! We help our business members connect with quality conservation partner organizations all the time. We would love to help you!